Video can often convey emotion and information more effectively than a static article. It can be an engaging way to start a presentation or to demonstrate a complex task. However, finding the best video for a certain topic can often be very time consuming (trust me!). While there are many great videos online, many of the videos on this topic present misinformation (e.g., the wrong way to add alternative text in MS Word) or are presented without captions themselves.

This post includes links to the most accurate, engaging, and accessible videos that I could find after hours of searching. Unless specified otherwise, videos are captioned and are found in YouTube.

Experiences of users with disabilities

People are far more inclined to make their content accessible once they realize how their design decisions can help real people with disabilities. If you only have time to share one video, make it a firsthand account from a user with a disability.

Created by GOALS

Students and faculty with disabilities share their frustrations with inaccessible web content in higher ed as well as their optimism that things can improve.

Created by WebAIM

Three users with disabilities (blindness, quadriplegia, deafness) demonstrate their frustrations with inaccessible web content. The technology used is a bit dated, but the experiences are very relevant.

Created by

The first half of this video (especially the first minute) provides excellent examples of students and faculty with disabilities.

Created by DO-IT

This is a fabulous resource for web developers and other more technical individuals. It explains the four principles of accessibility that form the foundation of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0. It has dozens of examples of users with disabilities interacting with web pages, and uses audio descriptions, which may be new to some viewers.

Created by Tommy Edison

The always humorous Tommy Edison shows how he uses an iPhone. After watching this video, take a few minutes to watch one of his Blind Film Critic videos.

The importance of accessibility

While many people may think it is a noble goal, they may not be sold on the importance or value of accessible web design. These videos help outline why web accessibility is a smart, fiscally responsible decision.

Created by FaHCSIA (the Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs)

An engaging, jazzy (maybe too jazzy) introduction to web accessibility. While the references and statistics refer to Australia, the principles are universal.

Created by DO-IT

While a bit long, this video provides a very compelling case for accessibility from Administrators in higher education. If you are struggling to win over administrators at your institution, this is a must-watch.

Creating accessible content

I had a great deal of difficulty finding tutorial videos that were accurate as well as timely.

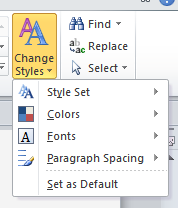

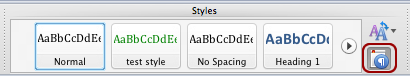

Created by Microsoft Office

Although this video is not captioned, it was the most accurate and up to date video I could find. Many of the best videos for creating accessible content are provided by the company itself.

Created by Adobe

A brief overview of how to use the “Make Accessible” wizard in Adobe XI. Adobe has an excellent “Accessibility Channel” for many of their tools. Unfortunately, not all of these videos are captioned.

Created by Rhett and Link (no captions)

Do you know someone who thinks that YouTube’s “Automatic Captions” are the answer to their captioning problems? Show them this humorous video. Ironically, I was unable to find a good video on captioning YouTube videos.

What’s on your playlist?

Is there a video that you regularly use that isn’t on this list? Please share it below.